Interview by Patrick Abboud

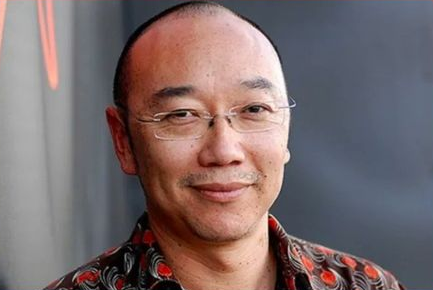

Award-winning writer, producer and director Tony Ayres is one of Australia’s great success stories. His accolades come from decades of commitment and dedication to his craft working in the increasingly competitive film and TV industry. Tony’s childhood was difficult. Born in 1961 in Macau, a Portuguese colony that has since been handed back to China, Tony never knew his father, and when he was three, his mother married a sailor who was visiting from Australia. That didn’t work out too well – Tony’s mother decided to leave her Australian husband soon after and the family suffered. She went on to become a nightclub songstress and that meant constant moving around for Tony and his sister. The family didn’t have much, they were sometimes penniless. Life was tough on Tony’s mother. She tried to take her life several times. Not long after his 11th birthday, Tony had to say goodbye to his mother. She died by suicide. His experiences of deep loss and family tragedy have shaped his approach to storytelling. Now entering his sixth decade of life, Tony reflects on how he went from orphan to orator of some of our most compelling and original stories on screen.

Patrick Abboud: Where do you feel that your creative career really kicked off?

Tony Ayres: I think, for me, it always starts with the impulse to write and, it’s about the impulse to write as a way of dealing with difficult situations. So it was trying to understand how I was feeling as a teenager. Being in love with a boy for the first time, I used to write poetry and talk about it that way. Coming from a very traumatized childhood with my mother’s mental health issues kind of overshadowing our entire experience of being in Australia, I tried to understand that, through writing. The motivation was trying to understand what was happening and then putting that out into the world and seeing whether there was an audience for it or whether the way that I expressed it was in any way useful to anyone else. Because I realized that the things that I was experiencing and feeling, and the way that I talked about it, were things that other audiences could connect to. And, so therefore I had the chance to make a living out of it.

PA: You’ve made everything from comedy to drama, to documentary, you’ve done installation work too. Are there common themes that you can see now standing outside of the work?

TA: The work started very personal. It was stories about my mother, my sister and I. And so it was stories about being a Chinese migrant in Australia in the seventies. And that personal, imperative continued on with stories about being gay and then stories about being male and then stories about being gay, male and Chinese, you know, trying to grapple with all of those things, very close identity-based works. And then as I developed more confidence in my storytelling skills, I started looking at other kinds of stories. I was always drawn to worlds that I didn’t know, worlds that I hadn’t seen before. And that’s a recurring thing in my work. I felt both a personal interest, but also sort of some kind of political imperative to tell Asian Australian stories. Because I felt and I still feel that these stories are vastly underrepresented on screens. So I look into that territory and the stories always tend to be about the complications of being human, the messiness of it. I’m interested in human contradictions and the difficulty of the human predicament. And the other thing is, I’m drawn to social justice, the things that I think are important to talk about in our society. One of my big recurring themes at the moment is the intersections of class and race. Trying to sort of see where our society is unjust or unfair, dealing with people who are at the bottom of the pecking order.

PA: ‘The Underdog…?’

TA: Yeah the underdogs… I think that’s it exactly! It’s also about empathy. What we’re trying to do is get into the skin of another human being. Drama is about writing other people’s points of view of the world. In order to do that you have to be empathetic and compassionate and that is how we can contribute to any particular subject. What I try to do is use the decades of working in drama to apply craft to a subject matter. Through craft you can hopefully speak to other people, and the more you do, the more you learn about what works, what doesn’t, how to connect to an audience, the ways you can structure a story to have a particular kind of impact. I feel as though I’ve gotten better at doing that and I feel like I’ve been able to speak to broader audiences as my career has progressed because I’ve learnt how to do that. It doesn’t come naturally at the beginning of your career. So, for me, it’s always a matter of what can you say that hasn’t been said about this subject. What is it that moves you as a human being – because it’s ultimately the emotional imperative that drives me as a creator.

PA: There’s such a lack of it empathy in the wider Australian media landscape! Thinking about how that sense of empathy really opens people up and makes us more receptive to other humans, where are the holes in the screen industry that need to be filled so there’s more of that and we’re helping Australians to get along better? that’s the power of storytelling right?

TA: Absolutely! I’m a hundred per cent in agreement. I’m not so great at knowing globally what is missing or isn’t from our screen industries. I think where we’re suffering as a society is we are in an increasingly polarised society where people just get their information from, you know, different epistemological systems. And so our ability to speak to one another is becoming increasingly fraught.

PA: What about specifically around cultural diversity, inclusivity, representation – they’re all words we’ve both spoken on hundreds of panels about – where are we on the diversity issue right now?

TA: I actually think we’re in probably the best position that I’ve seen in three decades of working in this industry, just in terms of the number, the sheer volume of creative people that I’m meeting, who come from different backgrounds. Five years ago I would have said, oh, you know, it’s all lip service, nothing has changed, but today I think that things are changing and I think they’re changing rapidly. And I think we’re getting a whole range of different stories. And I think that’s exciting. It’s an exciting time. I look back to 30 years ago and, really, I could count the number of Asian Australian filmmakers on one hand. And I knew them all. And half the time I was mistaken for one or the other of them! But now there are dozens and dozens of emerging writers and directors.

PA: How do you think that’s happened?

TA: It’s very bureaucratically led and it’s also led by growing political awareness within corporations. Australia is a very bureaucratic system. So the government bureaucracies like Screen Australia or Victoria, all of those funding bodies have a huge influence on the output, or what gets made here. And, at a certain point in history, recent history, they all turned their gaze towards, the lack of representation, both in front of the camera and behind the camera. All of those organizations suddenly started talking about diversity and inclusion, which kind of shocked me. It also amuses me because I’ve been working in this field for three decades and suddenly I’m in these meetings with white people who are lecturing me about how important diversity is.

PA: Oh God, I hear you…I can tell you about some very recent experiences around that story I’ve had…even just a week ago…

TA: Yeah, yeah. And, you know, I sort of still think, well, that’s a small price to pay for the fact that this seems to be a shift.

PA: There’s a groundswell, isn’t there?

TA: It feels like there’s absolutely a groundswell, which wasn’t there before. And you know, it’s phenomenal and nothing happens overnight in this business. You know, you have an idea and then if you’re lucky, five years later, it makes the screen – if you’re lucky! But I think in the next five years or a decade, I think we’re going to see this huge explosion.

PA: I brought that up because I think your work has played a really big role in that. I mean, take something like ‘The Family Law’, what other program have you ever seen on an Australian screen where the majority of the cast are all Asian or Asian Australian?

TA: Yes. Very, very rarely… in the world even. And also, you know, that it’s not necessarily about being Chinese or Asian, it’s just about… ‘the Australian experience’. That’s what I love about that show. It’s about how you can contribute to this current conversation, any cultural conversation that you’re a part of. You know, we work in a very resource heavy industry. And so you’ve got to be very clear about the purpose of why you’re doing it otherwise it’s just a waste of resources.

PA: You’ve been working for a few decades, you’ve made so much…where are you at, in your trajectory now?

TA: I’m tired and exhausted! [laughs]

PA: [Laughs] Of course you are! Apart from being tired and exhausted?

TA: A couple of years ago I left Matchbox, which was the company that I set up thirteen years ago. And I decided that I wanted to focus more on international work. And so now I’ve got a show coming out on Netflix called ‘Clickbait’, which is set in Oakland, but we shot it in Australia. I’ve got a couple of new projects, which are much more internationally focused. There’s always going to be some recurring imperative of a story that moves me. I’m currently working on a show for SBS, which is about Middle Eastern men, violence, masculinity and that’s a subject that is very interesting to me. I’m working with Osamah Sami and a number of other really interesting Middle Eastern filmmakers on this topic. If we get it right, I think it will be amazing and it’ll be very original. So there’ll always be something like this, you know, a smaller project, something that’s a bit of a side hustle, which will be me trying out new ideas, but then in the midst of that, I also need to make a few big shows to take risks. It’s always about what you haven’t done before, what you haven’t seen before, where you feel your contribution to any particular debate is as well. You know, all of those things.

PA: If you were to look back at your work today and imagine it was a sort of retrospective in a gallery, what’s the one project you’d put up front, your sort of signature piece.

TA: In some ways ‘The Home Song Stories’ is the one that is the most personal and the most, meaningful to me, just because it’s my family story. It’s a homage to my sister and that’s important. ‘The Slap’ was probably my first really successful TV show. I think it opened a lot of doors for me, as a creator. I guess those two, and then there are personal favorites, like ‘Sadness – a monologue’ which was a documentary I made with William Yang. It’s probably one of the simplest things I’ve ever done. And one of the few things that hardly anyone’s seen. Everything has it’s place in your heart. It’s hard to identify any one thing.

PA: What would wiser more experienced Tony say to that Tony, you know, who was starting out a few decades ago? Is there a golden lesson?

TA: With the wisdom of hindsight, I think that what you learn as you go along is that your identity is not necessarily embedded in your success or failure as a filmmaker. That’s just part of who you are. Another part of who you are is your success or failure as a human being. And that it’s actually about the kindness you show in life and in the relationships around you and the people you love. And, ultimately that’s always going to be the most important thing. And you just have to remember that and keep perspective, because sometimes when you’re working in what feels like a high stakes industry, and certainly when there’s a lot of money at stake, everything feels life or death but it’s really not. It’s like, life or death is life or death. Everything else you can get over, and almost always I’ve found that you can solve problems.

PA: Tony, as someone who moves through the world with their heart, which is so beautiful and really rare, do you still find that you have conflict with your head and heart?

TA: Sometimes you can take on projects for cynical reasons and the only way that you can carry on with those projects, if you will, is if you learn to invest in them. Head and heart always have to go hand in hand for me, ultimately. The most successful projects are where there’s both, where it has something to say, and it has something to feel, you know, those things together are the sweet spot, otherwise I can’t work on it. No matter what the form or, you know, no matter what the genre or the, the budgets or whatever’s at stake, let’s have it as both those things working together.

PA: Somebody who I really respect and admire very much said to me once what you do, day-to-day, doesn’t really matter so much. It’s about the traces you leave behind, you know, and the mark that you leave. What are the sort of traces that you’re leaving? Can you see that emerging through the work that you’re creating?

TA: I’m about to turn 60, so that’s a big change in life. And it’s a new chapter in life, there are all kinds of new things that I’m going to have to face over the next couple of decades, all about mortality and finitude. And, you know, I don’t think that’s a bad thing. I also realized that, we work in an industry where there is a lot of ageism. Having lived a life where I’ve dealt with issues around race, around sexuality, issues around class, I see ageism as the new thing that I’ve got to deal with. I guess I’m up for that discussion, for the kinds of biases that come your way from being in a certain age in our society. I think it’s a very Western thing because in most of the Asian cultures that I’m aware of and Indigenous culture, First Nations cultures, to be an elder is to be respected. Whereas I think Western cultures are particularly good at tearing down subsequent generations. But also as part of entering this new decade, you do have to think of what you’re going to leave behind. And so I do think, how can I help other filmmakers for instance, you know, how can I help support other filmmakers who are on a path that I recognize and how can I support talent that I particularly warm to.

PA: You’re doing that right now.

TA: [laughs] Yeah, I think about that a lot, you know how we get people to connect to each other, look at each other. And, you know, it’s really, really simple, you know, drama when it really affects people, gives some people something to talk about. Like everything that we do is about what are the things that connect us as human beings. And I think that those messages are really important.

First published in Sydney Review of Books on March 14, 2022. Article commissioned by Diversity Arts Australia for the Pacesetters Creative Archives project, which was funded through Create NSW.