This conversation is also special, in that we first worked with each other 30 years ago, at a time when there was an expanding wave of Arab-Australian contemporary artists and cultural production.

Our conversation winds through reflections around sawt/voice, theatre work, media work, absence and presence, humour, Blackness and Arabness, being a Pacesetter. It was conducted in English and Arabic, with translation and transcription provided by Nesrine Basheer, Mariam Farida and Rayan Alan.

This piece reflects language and laughter that moved between Arabic and English, with code-switching in-between. I learned of the iconic significance of Sawt Saleh/Saleh’s Voice – so it feels important for his words to speak for themselves (and for me not to craft an essay about him).

Within this piece we cannot get the resonance of Saleh’s voice in Arabic, as we are reading translations, transliterations and transcriptions . However sometimes we are reading the rhythms and structures of Saleh’s voice in English.

– Alissar Chidiac

Sawt/Voice

Alissar: In anticipation of doing an interview with Saleh, I had the instinct to focus on an experience with ‘resonance’ and his ‘voice’ – not about the vibrations between his bass and treble, but about the diasporic phenomenon where ‘time is compressed’.

I remember a unique moment at Bankstown Arts Centre in Sydney, Australia in 2013, after an Arabic language performance of Burra Wa Ba’eed, a bilingual performance that we both created. An audience member had spent half the performance wondering why Saleh’s voice was so familiar. He then realised he knew that voice from his own childhood in Amman.

Now, one generation later, that audience member was with his wife and his child, in a land on the other side of the planet, hearing that same voice again in a performance about cancer and stigma. I asked Saleh about his voice travelling through time and space.

Saleh: This man was hearing something from the 1970s, early 1980s, when I was living in Jordan and working as an actor, in theatre and TV. He remembered my voice from a children’s program called Qaws Qusah/The Rainbow. It was an educational program for ages between four and nine years. We had SemSem and FellFell. My character was SemSem who was very slow in thinking and talking.

I also did storytelling, reading children’s stories in a way that was engaging. I would give a tone to each character – if there was a character that was older, younger or an animal, I would do the voices.

Voice for me is a talent. God has given me the talent of voice. Voice is my main resource. It is something that if I lose it, that is it, bye-bye, there is no work. For this reason, I take care of my voice. I have two kinds of voices: the warm voice and the melodious voice. I can play with my voice how I want. When I want to tell a story, I use tone for that. In theatre when I would do a character, I would have a specific tone in my voice. I let my voice from the inside do its thing.

In Jordan, all my work was in Arabic.

However, when I came to Australia, my work needed to be in English. That voice didn’t give me the feeling that I had reached the message I wanted. I used to be very comfortable speaking in Arabic, because I know my tone is loud, soft, middle, whispering. My voice didn’t change from when that friend in the audience and his son heard me. It might have increased a little in base, with age, however it is as it was.

With my voice, I have employed myself in acting, in presenting the news – presenting programs on the radio, presenting news for Al Jazeera and other channels, and doing voice over work. The most work I’ve done as a voiceover was with the Walt Disney production company in Singapore. My voice became known in Disney as ‘Saleh’s Voice.’ Lots of people used to tell me, ‘We heard you on Disney’. The people who used to hear me in Jordan were now hearing me on Disney.

When I worked with Al Jazeera in Australia making television reports, people also said, ‘Weren’t you also in Jordan with your voice?’ People would begin to tie the voice to Saleh and not with a person or an organisation that I was with. ‘We heard the voice of Saleh’.

Even now, my voice on the phone, whenever I make a phone call, even if they don’t know me but they speak Arabic: ‘Yeah, Mr Saleh, how are you?’ I ask: ‘How did you know it was me?’ They say: ‘Of course, your voice is known.’

Theatre work

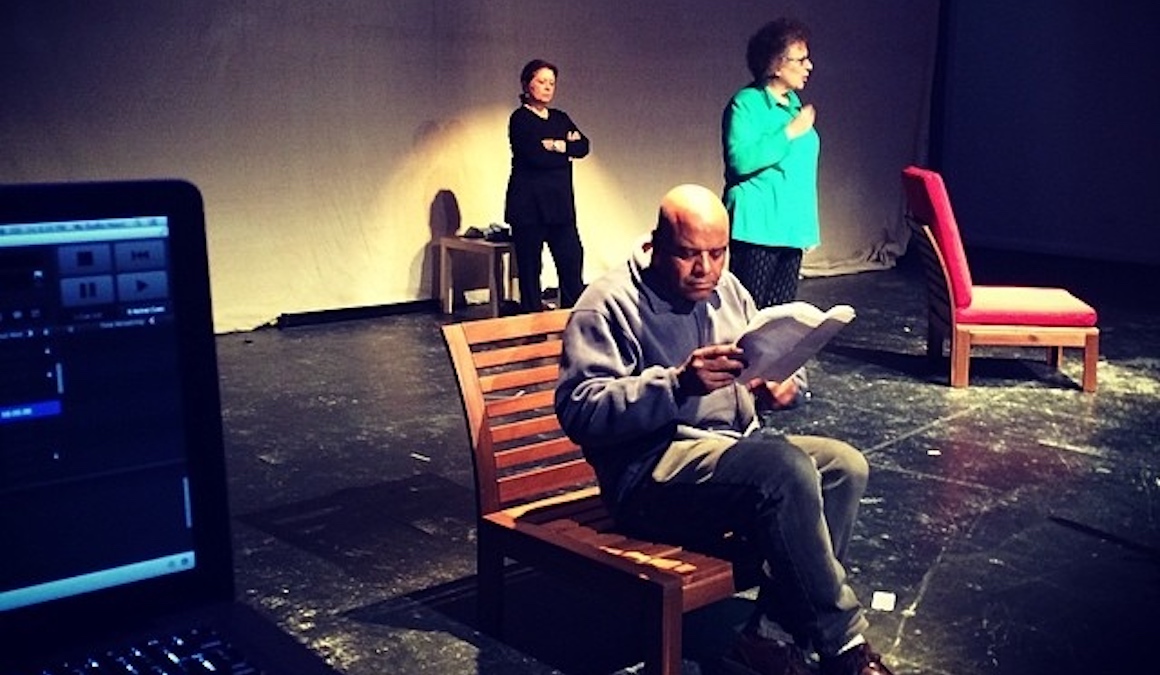

Alissar: I first met Saleh through Taqa Theatre in 1991, a Sydney-based Arab Australian contemporary group producing work throughout the 1990s. I asked Saleh about Taqa. It had opened him up and developed a love of collaborative and self-determined theatre-making.

He also went into solo work, and I have a strong memory of his charismatic presence in The Man Who Lost His Shadow. I asked about his reflections on different practices of creating collaboratively and creating as an individual. Saleh also worked on many community arts and community education programs, especially with his voice in Arabic. Bilingual work is important to him – he sees language as identity, as the ‘last resort’.

Saleh: Taqa Theatre was the starting point for me for theatre in Australia. I was really happy to meet these people and we started working [collaboratively]. Something new for me, I didn’t know the process of how they worked here in Australia. I remember when I was Jordan, somebody writes a play and gives it to us: this is the play, we have to do this one.

When we talk about the word ‘Taqa’ in Arabic it means ‘Al Qamareya’ – and that’s what we called our first play, Al Qamareya. It’s the little window at the top of the house, in the old houses. ‘Al Taqa’ could also mean ‘energy’. But for us, both meanings reflected what we were doing, because when you look at Al Qamareya, there is a light. This light coming from Al Qamareya drops somewhere and reflects on something else. Energy does the same things.

It was interesting to work with different generations of performers, most born or grown up in Australia. And their Arabic is not good, so for me, I was happy, because sometimes they could ask me ‘What do you mean by this?’ And I could ask them. We worked together to understand each other. It was new for me to work with a group. I learned from working together because some of the issues were not clear for me. I learned how to communicate with people together, how to respect their ideas, and how they listened to me. That’s why I am proud of Taqa and I kept my friendship with many of the members until now.

Media work

Alissar: With the depth and the layers he had in speaking in his Arabic voice from ‘the inside’, this led Saleh to spend half of his life, maybe more, working in media, including Al Jazeera in Australia. Listening audiences knew his voice over many years. In return, he actively knew multiple layers of networks, activities and individuals within Arab communities.

Saleh: When I was working in programs interviewing people, always in my mind was to have fun. I needed fun because we are not just informing people, we have to entertain people.

I started a gardening program on Sundays. Lots of listeners in the morning enjoyed it. Talking about the lemon tree in the corner not doing anything, it’s nearly dying: ‘What can I do about it?’ ‘These roses are not having any flowers.’ I succeeded because I chose good engineers to talk to the program, they gave advice to the people. They spoke their language and they made it easy for everyone.

The funniest things happened to me. One day we started talking about animals. Chickens and domesticated animals. Roosters are not allowed in people’s houses you know, because in the morning it starts and not many people are happy. This listener called me and said, ‘Look, I have a solution for my rooster. Look, what’s happening, is when he sleeps at night in the cage, I cover the cage with blankets and it becomes dark, and when it’s dark the rooster doesn’t really make any noise, and so I keep the blanket on the cage until 9:00 in the morning and the rooster still thinks that it is night and doesn’t make any noise.’

We went to his place and we had lots of fun. He managed to escape from the council issue about not having the rooster. A sense of humour you need always.

Arabic language

Saleh: For me, the Arabic language is something important. I trained myself to keep using my language, despite being in Australia.

Our Indigenous people here in Australia work hard to keep their language. We as Arabs, the last stronghold for us is language, there is nothing but it. We have to keep telling our stories, we have to continue our culture through our language. That’s why I always insisted, when I was working in theatre, to enjoy working in bilingual theatre, speaking Arabic and English. To try to educate people about our language. Music, it’s a language, and everybody knows when you play something, and understand what’s going on. Same with language – if you keep using it, many of your audience and listeners will become familiar with it.

When you talk about the Arabic language, our voice when you use our language, we use the tongue, the throat, the jaw, the lips, the breath, all these things. When you go: “tha-tha” or “gheen-gheen” or “kha-kha”. These sounds of Arabic letters. And we talk about your breath and how you use your breath.

So I put the question: Is there Arabic breathing? Do I breathe one way in Arabic and another way in English? Or maybe there is bilingual breathing? Maybe in Arabic, I breathe from right to left, as we write. And in English, I breathe left to right. I just put my finger here – what am I breathing now if I block one part of my nose? English or Arabic? I don’t know I have to think about it.

Talking about bilingual breath, the other day I was driving my rusty Datsun 120Y in Western Sydney.

I must admit that my speed was over the limit. The car radio-loud, playing Arabic music, was like a nightclub. The loud music made me drive like a maniac. Suddenly out of the blue, the police stopped me and said:

‘G’day mate, have you been drinking?’ I said: ‘No, I’m a Muslim, I don’t drink.’

‘That’s nothing to do with your breath testing. Please count to ten.’

I started counting. ‘Wahad (one), Tneen (two), Thalatha (three), Arba’a (four).’

‘Stop, Stop, Stop,’ the police said. ‘What are you counting?’ ‘I am counting in Arabic.’ ‘I want you to count in English.’ ‘Do you think I am cheating? Do you think I am counting five, seven, nine, two, nine, one?’

‘Listen, mate, you are not allowed to count in another language.” “Why? Do you think I can be over the limit in one language, and under the limit in another?’ ‘Mate, this is a strange machine, it only understands English. Count slowly.’

‘One, two, three, four…’ Ohhh, I don’t know why they cannot invent a bilingual breathalyser?

Blackness and Arabness

Alissar: I’ve never heard Saleh seriously speak about his experience of ‘Blackness’ and ‘Arabness’ and so this is a unique opportunity.

Saleh: I am proud that I am Arab. For me personally, it doesn’t matter what country I am from. I am Arab. I speak the language. I am happy to speak my language and I speak it wherever I want. I am also happy that my colour is dark, brown or black. A person needs to be proud of themselves.

In Jordan, there are people of my colour, there are blonde people, there are white people. Maybe there are people who still have the image of the word ‘slave’ (in Arabic) about people with dark skin. This word hurts people. I was very strict with these things. I wouldn’t let anyone speak these words at all. You have a colour called dark or black, speak like this. But the word ‘slave’, when you interpret it in Australia, is racism, clear racism. Even though people there take it for granted, people say it, no big deal, they laugh.

One thing till now that upsets me, was when I worked in a series on Jordanian television.

The producers and directors put you in a specific picture: this guy is Black, he has a specific role – he can be either the servant of a sheikh of the tribe, if he was a bedouin, making the coffee, or a messenger of the king, or the prince in a historical series. Or, if it is a religious program, they would give the role of ‘Bilal’ saying “Allahu Akbar”. Bilal is the first one who said the Adhan in the era of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) and Bilal is Black. They put you in this category.

One day I spoke to a producer, who is a friend of mine: ‘Why did you give me this character in this series?’ He tells me: ‘It doesn’t work for you to be put into a romantic role.’ I was shocked. This is the only incident this happened to me. Since then, I said: ‘Look, anything coming in the future, in a series, where they give me a role which fits into this frame, I don’t want it.’

When I came to Australia I didn’t know about multicultural society, then gradually I learned many things. I found talented people from all nationalities, of all colours. I was very happy to see this. They gave me an opportunity to make a children’s program that I was responsible for. Something I felt proud of. Then when I came to Taqa Theatre, we worked together, and I didn’t feel there was anyone who was saying ‘He’s Black, or he’s of a certain colour.’ Everyone speaks the language, we work together.

Legacy

Alissar: Before winding up, let’s reflect on one statement: ‘Everybody leaves their mark’.

Saleh: In all the projects that I have participated in, I have proved to people that I could do it. I have done it. If it was a voice-over, I know what they want, I have studied and done my homework and given what they want.

When I worked in radio, I taught my friends to be flexible, to move a little bit, not be restricted or to be careful about grammar, how to talk when we ask questions. We have to be normal. The listener cannot see me. There is a barrier between us. They hear my voice, but they can’t see what I’m doing. I have really to portray it, to describe a picture of how we are in the studio.

Even with my speaking, in my voice, a laugh, a word. Even with the news, sometimes if you put a funny story right at the end—after all these wars happening and all this bloodshed going on everywhere in the world—at the end of the news, you give people some hope. I’ve told people that we could not only use our talent in reading the news or our voice, but we could really change the atmosphere in our voice and make something for people. Make people happy.