Words: Kean Wong

Looking back now, it was the most spectacular cultural event seen in Indonesia’s capital Jakarta in a generation. It had the modern energy of a fabled rock festival moment in the West, mixed with the hopes of freedom that, for one Javanese night, resisted the decades-old Suharto military regime. Yet none of the energised festival-goers could have predicted they were sparking the final decade of resistance to a brutal, often bloody New Order regime that would end a few years later.

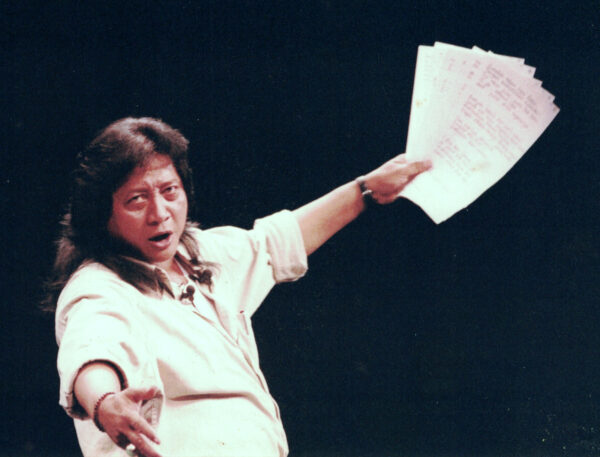

For singer-songwriter Sawung Jabo, now in Sydney, those sweaty nights in huge Indonesian stadiums in 1990 have stretched into the artforms he still practises in Marrickville today at age 70. There has been a continuum, in threads of sounds, music, theatre and poetry that have been his trusted amulets linking Sydney, Yogyakarta, Jakarta, Bali, and Surabaya over his decades of creative endeavour. Born as Muhamad Djohansyah in Surabaya in 1951, his stage name Sawung Jabo has long become his indivisible persona.

Although he moved to Sydney in 1994 with his Australian family, Jabo, as he’s popularly known, has regularly returned and worked on projects in Indonesia up until the pandemic closed the borders. But if his projects across Indonesia are marked by the rock stardom that launched him to prominence in 1990, Jabo’s Australia-based work has been more mixed, as much a comment about Australia’s alienation from its region and giant neighbour Indonesia as it is about how the arts and its audiences are stratified between elites and the rest.

Jabo and his work in Australia is critically, rather than popularly, acclaimed in music, theatre, and film; whether that’s in startling bands he co-founded in Sydney like the Turkish-Indonesian fusion of GengGong; in ground-breaking productions for Sidetrack Theatre and Belvoir St Theatre that have also toured Indonesia; or co-starring in remarkable films that captured their eras like ‘Lucky Miles’ and ‘The Year of Living Dangerously’. Throughout his Australian trek over the past 40 years, Jabo always connected the dots, linking Indonesia to Australia’s ancient past. His songs and theatrical work connect with the indigenous songlines that map our shared realities, stretching beyond suburban Sydney into the deceptively stark landscapes he found in northern Australia.

When we meet in Sydney in 2021, Jabo was again revelling in the process of collaborations and his daily rituals of arts production. He was about to start workshopping a performance work that will be part of Indonesian-Australian artist Jumaadi’s show later this year at Adelaide’s OzAsia Festival.

But in 1990, Jabo was in a different realm. Indonesians were restless for a new decade of freedom, demanding liberation from the stifling (and worse) Suharto regime. Jabo had welcomed that new decade with the warm reception for Swami’s debut album, a collection of songs produced by the music group he co-founded with youth icon Iwan Fals. That eponymously titled album became a huge hit, selling well over 100,000 copies and making them rock stars. I had met Jabo and Iwan for the first time in Jakarta soon after that grand debut, and had used a rough Western shorthand to place the pair for a foreign context. To their amusement, I contrasted Jabo as the ‘Bruce Springsteen’ to Iwan’s ‘Bob Dylan’ , yet in a sprawling new nation, they were much more than that; much later, Rolling Stone Indonesia framed them much the same way.

Like Jabo’s previous projects in music and theatre since the late 1970s, when he graduated high school and enrolled at Yogyakarta’s music academy, the national successes of the 1990s, after the Swami breakthrough, was still all about the praxis. Despite the huge commercial success of his subsequent ‘supergroup’ Kantata Takwa – its debut album reportedly selling over half-a-million copies – for Jabo it was still the process of making art that held core meaning for him.

It had led him to form the band that was also a ‘workshop for ideas’ called Sirkus Barock in the arts capital of Yogyakarta. And Sirkus Barock continues 40 years later. Jabo said he was deeply influenced by the famous dissident poet and playwright W.S. Rendra’s Bengkel Teater (or ‘workshop theatre’) when he joined as a wayward music student in 1977. Rendra’s Bengkel had survived the military regime’s censorship, bannings and jailings, and at its heart was divining art and meaning in the process and practice of theatre. It was a huge artistic force in Yogyakarta and across Indonesia at the time. Jabo’s lifelong friendship and collaborations with Rendra began about then. It was also there that he met Suzan Piper, a fellow student from Sydney who he later married and has been his lifelong collaborator.

But in 1990, Jabo’s praxis was centred on Swami, wielding Javanese percussion and wind instruments, and charged with electric guitars and the sonic boom of its much-lauded rock rhythm unit. The group Swami created and performed the ground-breaking songs of resistance, transforming the group’s twin lead singer-songwriters Iwan Fals and Sawung Jabo into the rock stars of Indonesia’s 270-million-strong archipelago.

And yet Swami was more than Iwan’s and Jabo’s band. It was an ensemble that soon morphed into the rock spectacle that was Kantata Takwa, a so-called ‘supergroup’ that not only featured W.S.Rendra but also rock impresario, and sometime oil tanker tycoon, Setiawan Djody, keyboard whiz Jockie Suryoprayogo, bassist Donny Fatah, and the Javanese drums maestro Innisisri.

It was this ‘supergroup’ that produced those magical nights of theatrical rock music intertwined with a modernist Javanese poetry at Jakarta’s historic Senayan stadium in June 1990. More magical nights followed in eastern Java’s sprawling trading metropolis of Surabaya that August, and the ancient city of Solo in September. Those who couldn’t fit into the venues celebrated outside, swelling the crowds to 350,000 in Jakarta to about half that in the other cities. The Australian folk/jazz musician and teacher Margaret Bradley was there that June night in 1990, at Jakarta’s Senayan stadium, and still remembers vividly how the city was “on edge”. After several violent crackdowns by the military regime on civilians in the weeks leading up to the concert; the atmosphere was “simmering to the boil, all vibed up,” she recalled.

The songs were popular among young Indonesians rebelling against a corrupt military regime, and it was a type of modern poetry that many identified with. For many, it was the first time Western rock music and its urgent pulse was melded to the burgeoning Indonesian narrative for democracy being forged on the streets of its cities.

Songs like ‘Bongkar’ (Tear It Down), ‘Kuda Lumping’, ‘HIO’, and ‘Bento’ also came across like a new decade’s musical articulation of Rendra’s dissident poetry and theatre, that had been banned by General Suharto’s regime throughout the 1970s. Although the Suharto regime was seldom ever namechecked on stage, the Swami and Kantata Takwa audiences immediately understood the stories told in songs about dispossession, corruption, and the hypocrisy of the ruling class. These were songs that came to characterise the ‘reformasi’ (or democratisation reform) movement led by Indonesian students that triumphed in 1998 amid the Asian Financial Crisis, which forced General Suharto from power.

Still huge, and still spoken about today as a pivotal event when Indonesian culture changed for the better, fleetingly liberated by rock music, and inadvertently loosening the constraints of the New Order military regime’s decades of authoritarian rule. Those hot nights kicked off the decade, ending Suharto’s 33 often bloody years in power by its end.

Today, the Swami and Kantata Takwa songs Sawung Jabo co-wrote and performed like ‘Bongkar’ (Tear It Down), ‘Bento’, and ‘HIO’ are still part of democratic Indonesia’s street soundtrack. The songs from the Swami and Kantata Takwa albums are invoked and sung along to decades later by new generations of students and youth demonstrating against threats to Indonesia’s hard-won democracy, defending their rights and protesting against corruption in their tens of thousands against current President Joko Widodo.

Released nearly three decades ago, the songs still feel relevant today. Their playful sarcasm about class divides, while poking fun at feudal loyalties, stifling traditions, and Javanese mysticism still resonate with lyrical imagery and calls to action. Often hummed by audiences as popular choruses and sound bites, the songs use the individualistic directness of rock music to rally a contemporary resistance to dictators and fraudsters alike.

Jabo is typically modest about how these songs, which he co-wrote with Iwan, have become ‘reformasi’ anthems, explaining again how making art that resonates with “the common folks” is a continuous process for him. It’s the praxis he has lived by since he started busking for a living straight out of high school, on the mean streets of Jakarta and Yogyakarta, living and learning the stories of petty criminals, mobsters and sex workers around him, something he shared with Iwan Fals’ own background as a street busker.

“Because I was partnering with Iwan Fals, who was a superstar and who loved the kind of music I did,” Jabo explained, “we ended up writing songs together that became big hits. We protested the militaristic totalitarian (Suharto) government in our songs, and people agreed with what we were saying – they said ‘you represent us!’ We were so grateful, so honoured for that.”

As the 1990s unfurled and Jabo’s bands Sirkus Barock, Swami and Kantata Takwa won new popular and critical acclaim, he wound back to his singular artistic process by 1993, taking out the supergroup bombast of Kantata Takwa to make ‘Dalbo’ and ‘Anak Wayang’ with Iwan. He also released a sardonic solo album titled ‘Badut’, or ‘clown’, referencing the politics of the times.

It was back in Sydney that he wrote the songs that became Sirkus Barok’s ‘Fatamorgana’ album, presenting it live in Jakarta in 1996, when opposition to the Suharto regime was still rising. Then when mass demonstrations erupted against the regime’s crackdowns, corruption and killings amid 1998’s Asian Financial Crisis which forced General Suharto from power, the supergroup Kantata Takwa was ready and reformed to perform. The May 1998 riots across Indonesia were a bloody end to that decade’s turmoil, as cities like Medan, Jakarta, and Solo erupted in looting and violence, fuelled by anger over food shortages and mass unemployment and with the minority Chinese Indonesian communities sometimes targeted by shadowy military units. Over a thousand people died in the riots, and there were hundreds of reports of assaults and rapes carried out by gangs linked to the crumbling military regime.

The songs of righteous anger and activism that Jabo had co-written and performed with Swami and Kantata Takwa at the start of the decade were again being sung and screamed in unison at street demonstrations demanding change across Indonesia. The reformed Kantata group performed on stages supporting the students, despite the dangers at the time: “We were all worried about the snipers,” Jabo recalled at a recent Sydney gathering to mark his 70th birthday. “There had been so many reports of the (military) snipers shooting unarmed civilians across the cities, trying to kill the protests. And we were obvious targets. But we persisted, said our prayers together before we took the stage.”

In Sydney, looking back at those years that gave birth to today’s uncertain Indonesian democracy, and the crucial role Jabo has played in articulating that turmoil, he said that he’s grateful to have made music that has meant so much to so many at a critical time in Indonesia’s modern history: “I am a musician, I make music, I make art… I’m humbled when the people say we represent them.”

Following Australia’s controversial role in Timor Leste’s independence at the time, the political relationship between Australia and Indonesia had deteriorated, affecting artists like Sawung Jabo. As ever, Jabo was open-hearted – and his praxis was the key. “The crisis had a big impact on me,” he explained at the time to The Jakarta Post.

By the start of the new millennium, Jabo was spending more time in Australia. The opportunities for funded arts projects that enabled the talents of Jabo were few and far between, while the Australian disinterest in Indonesia and the region had seemingly grown stronger too. As film director Michael James Rowland explained in an interview about his 2007 film ‘Lucky Miles’, which co-starred Jabo as a boat captain stranded in northern Australia with his cargo of asylum-seekers, the Australian film world was possibly worse:

“I think theatre has a much better record of representing the true face of Australian society. By way of example: Jabo’s an Indonesian and the last time there was an Indonesian on the big screen was in ‘The Year of Living Dangerously’ (Peter Weir, 1982),” Rowland told Metro Magazine. “Is indonesia a big and important neighbour of ours? Yes, it is, so how do you explain that lack? In fact, Jabo was in ‘The Year of Living Dangerously’, but if you’re an Indonesian actor wanting to work in Australia it’s a long time between films. Whereas back home, he’s been described (by Rolling Stone) as the Bruce Springsteen of Indonesia. He’s an enormous pop star in his own country, whereas in Australia I think we often blithely turn a blind eye to the society we live in and to our neighbours. When did we last have a film with a New Zealand character, or one from Papua New Guinea?”

Meanwhile, making new music was still Jabo’s praxis. By 2000, he had formed the beguiling Turkish-Indonesian fusion band known as GengGong with Ron Reeves, Kim Sanders, and Reza Achman. GengGong made a unique, folk-friendly music that featured west Javan and Sundanese percussion with rock-steady electric guitars and drums, and the lively interventions of Turkish and Bulgarian wind instruments. In the mix were also traditional Indonesian mask dances and the loud theatre of gongs. Between July and September that year, GengGong toured Indonesia, featured at Yogyakarta’s renowned Gamelan Festival, and recorded their debut album, which was soon released to critical acclaim in Australia too.

“I never lost my optimism or sense of humour. I kept writing music through these times because that’s who I am. Indonesia is a never-ending source of inspiration for me. I am always inspired by everyday life. Anything, anytime.”

Making art, making music, anything, anytime. That has been Sawung Jabo’s true north. Sharing the joys, the challenges, and the grim determination to privilege the process of making and producing has been Jabo’s point all along. Australia’s late lamented Sidetrack Theatre’s founding director Don Mamouney once wrote about making and staging, with Jabo in 2004, a hugely popular Australian production of the East Javanese mythology of Sawung Galing. Describing “a wild and fantastic world where despots sow confusion and cultivate prejudices amongst the people to maintain their power and justify war”, Mamouney wrote of Jabo’s central role in getting this show on the road, that it was “magical… exceeded my wildest dreams”.

The show played to thousands of Indonesians, in cities and villages across Java: it was the process of art, after all. “We then took what was a show of circus proportions on the road; five trucks and two buses journeyed to Solo, Surabaya, Bandung, and Jakarta,” Mamouney said. “With the exception of Jakarta, we played to huge audiences. This was especially so in Surabaya (the home of the original story) where it was estimated that the audience exceeded 4,000. In Jakarta the show played to a meagre 600 or so, as the performance space was a sports field, only a few hundred metres from the Australian Embassy, which had been bombed exactly a week before. That night, the then-President Megawati decided to mark the tragedy with a visit to the Australian Embassy site, causing a traffic jam of Jakarta proportions and leaving us with a comparatively small audience, half of whom were police, the bomb squad and our own security people (all ‘black belt’ members of our fight director’s Silat group). We started the show late, partly in the hope that more audience would find their way through the traffic, partly for security reasons. By the time the show started, the only people who seemed to be taking their job seriously were the Silat group; the bomb squad had relaxed and were enjoying the show. Clearly Sawung Galing had become community theatre of a different kind. So stage one is complete. Now we have the challenge of getting Sawung Galing to Australia.”

But ‘Sawung Galing’ never made it to Australia, despite it being made in a rare and fruitful collaboration with Australia’s Sidetrack Theatre. For Jabo, in his 70th year, there are no regrets. Making art remains the only meaning left for Sawung Jabo. It’s the only way forward.

This interview with Sawung Jabo was conducted on the unceded lands of the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation.

First published in IndoMedia on 15 November, 2021. Article commissioned by Diversity Arts Australia for the Pacesetters Creative Archives project, which was funded through Create NSW.