Egypt’s El Dammah Theatre

Azza Guergues

“Historically, folk art expressed people’s sentiments and revived their hopes during times of adversity, such as wars and displacement. In the new era of economic openness, art became a commercial enterprise. I want to restore its spiritual value by establishing and sponsoring bands, producing albums and documentaries about them, and connecting them with other bands through international tours.”

Cultures back from the brink

-

Continuing cultureIbrahim seeks out marginalised musicians and encourages them to perform here in their languages and dialects, sharing personal experiences through music and preserving threatened traditions

-

Platforms for performanceBy providing a space to connect with mainstream audiences, folk bands have a reason to reform.

-

Online streamingRecording, archiving and sharing music connects marginalised ethnic communities with global audiences.

-

Financial opportunity

Providing a stage for marginalised artists has led to critical paid opportunities.

Wind your way down an alleyway in central Cairo and you may find the El-Dammah Theatre, which has presented diverse and displaced musicians to mainstream Egyptian audiences since August 2010.

Cairo’s El-Dammah Theatre entrance, which is located in a small alleyway, May 2022, photo by Azza Guergues

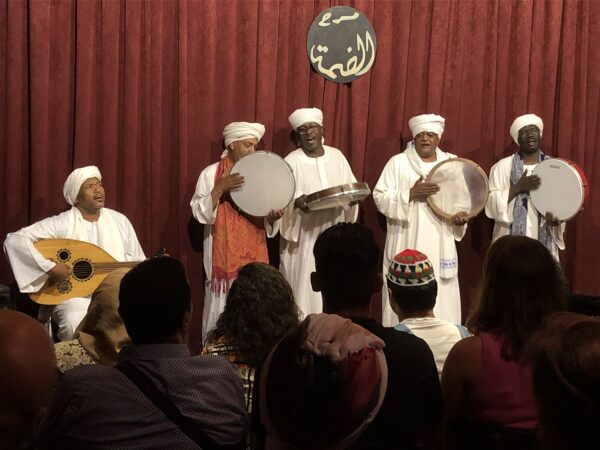

Egypt is a highly centralised country and communities like the Amazighes (west Egypt), the Nubians (far south), and the Bedouins (east) have long been marginalised. Musicians from these groups have found freedom of expression and diversity at the El Dammah Theater. Its stage is usually packed with both Egyptian and foreign audiences who come to watch and support the performances of these bands.

El Dammah Theatre has thrived for over 10 years, without any funding from the government. Ticket sales (US$5.30 per person) are its only revenue source. Folk musicians from different parts of Egypt have found a huge stage in this theatre, including Tanpura music from the Suez Canal region, Rango music from Sudan and southern Egypt, Nubian music, Sufi music, and Al-Zar music performed by women from low socioeconomic backgrounds. The theatre has been able to revitalise the traditions of many marginalised in this way.

Cultural activist: Zakaria Ibrahim

El Dammah Theater, which is also home to El Mastaba Center for Egyptian Folk Music, was founded by Zakaria Ibrahim, a 70-year-old cultural activist. He was born 280km from Cairo, in Port Said, eastern Egypt and his hometown was targeted by the Tripartite Aggression – where Israel invaded Egypt in late 1956, followed by the U.K. and France. As a child, he played the tambura and sang songs about the history of the area during the war.

When he relocated to Cairo in the 1980s, he was enthusiastic about decentralising arts and bringing music groups from other regions and ethnicities into Cairo.

Nuba Nour, a band from Nubia in southern Egypt, performed in the theatre on a hot Cairo summer night, June 2022, photo by Azza Guergues

Breathing folk music back to life

In a short time, Ibrahim was able to bring 12 different Egyptian folklore groups back to life and sponsor them to perform every week at the El Dammah Theatre for dozens of people.

While preparing for an El-Dammah theatre concert, Ibrahim said, ‘I did not want folk arts to disappear, so I invited old artists back to perform. I started a band with tambura in the late ’80s, and then went all over the country forming bands and inviting old artists back to perform.’

Egypt to the world: online streaming

To spread their art further, Ibrahim has recorded and posted around 800 videos of the groups’ songs and performances on YouTube so those unable to attend concerts can still listen to them online. Today, many of these bands can perform at overseas festivals and receive funding to continue creating their music.

‘Historically, folk art expressed people’s sentiments and revived their hopes during times of adversity, such as wars and displacement. In the new era of economic openness, art became a commercial enterprise,’ says Ibrahim. ‘I want to restore its spiritual value by establishing and sponsoring bands, producing albums and documentaries about them, and connecting them with other bands through international tours.’

Archiving and sharing oral heritage

On a hot Cairo summer night, the theatre hosted the Nuba Nour, a band from Nubia in southern Egypt. Nubians are the indigenous people of the area, but as Arabic has taken over education and society in Egypt, the Nubian language is on the verge of disappearing.

Nuba Nour is a great example of language and tradition being re-energised with support from projects like El Dammah. The band writes about displacement after the Egyptian government forced them to leave their villages in the 1960s to build the Aswan High Dam. They sing about nostalgia for their old homes and praise the Nubian language for surviving in Egypt after the Arabic language took over. Their songs portray their pride in ethnicity, skin colour and cultural heritage.

Osama Bakri, Nuba Nour’s leader, said the music group promotes Nubian culture and tradition through art. ‘The band was formed in the 1960s. We paused for a while, but we came back in the ‘90s. We participated in European festivals and toured many countries overseas. People are engaging with our music, and they ask what the songs mean. Our songs are about the Nile, palm trees in old Nuba, and love as well,’ he added.

Bakri added, ‘For future generations, we are committed to preserving the Nubian language through singing and poetry. While the Nubian language has never been written, many studies have been conducted on it recently, and they have written letters for it. El Mastaba Center enabled us to share our culture and traditions with Cairo audiences. Whenever we sing in our language that has existed for thousands of years, we feel so happy, and we hope that the generations after us will continue the journey.’

Financial opportunity

Zakaria Ibrahim says the theatre concerts he organises are well attended. Several bands that perform at El-Dammah Theatre have toured multiple countries and receive financial compensation for their performances. ‘People invite them to concerts and shows when they like the songs, which keeps the demand for the songs growing,’ he said.

Ibrahim’s success sends a clear message to the central government about the importance of preserving Egypt’s diverse heritage. Ibrahim’s efforts are vital at a time when Egypt’s minority cultures are under increasing threat. There has already been a loss of Coptic language and culture, as well as a loss of other cultures, and other cultures are facing the same fate. To protect these marginalised cultures and bands, there needs to be more policies and non-profits that help them to grow and expand.

Azza Guergues

| Azza Guergues is an Egyptian journalist and podcast producer, she has nine years of experience in the news industry. She has produced videos and podcasts covering topics such as politics, climate change, economics, and social issues in MENA countries. She has covered events in Kazakhstan, the United Kingdom, and Egypt as well as the war against the Islamic State in Iraq in 2017. Azza earned her MA degree in Digital Journalism at Goldsmiths, University of London in 2019. She is also a fellow at UNRAF and Chevening Alum. |

What is the Imagine Around the World Project?

A partnership with the British Council Australia, the Imagine Around The World Project aims to document case studies from numerous countries outside of US, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand to share best practice and leadership in cultural diversity, cultural equity and inclusion in the arts, screen and creative sectors. This project is managed by Diversity Arts Australia and supported by Creative Equity Toolkit partner, British Council Australia. To find out more click below – or read the other case studies as they go live here.