Anti-racism is a verb, not a noun

By Monique Choy

“I think this is particularly complicated – not just performing your identity but having to declare it in the first place. As a friend said to me the other day, I didn’t think of myself as different until an application form reminded me. If I tick the ‘culturally and linguistically diverse’ box, one door opens and another door closes; the door that closes is my ability to choose what I centre. I’m not diverse to myself, am I?”

Anti-Racism in Action

- Two-pronged approach: First acknowledge that creatives of colour are marginalised; then provide platforms for free expression

- Anti-racism means power-sharing: Band-aid measures to change language or collect data are not enough

- Centring anti-racism: Setting anti-racism as a foundation stone in an organisation is better than retrofitting existing structures

- Representation is not an end goal: It is a precondition for free expression and creative control

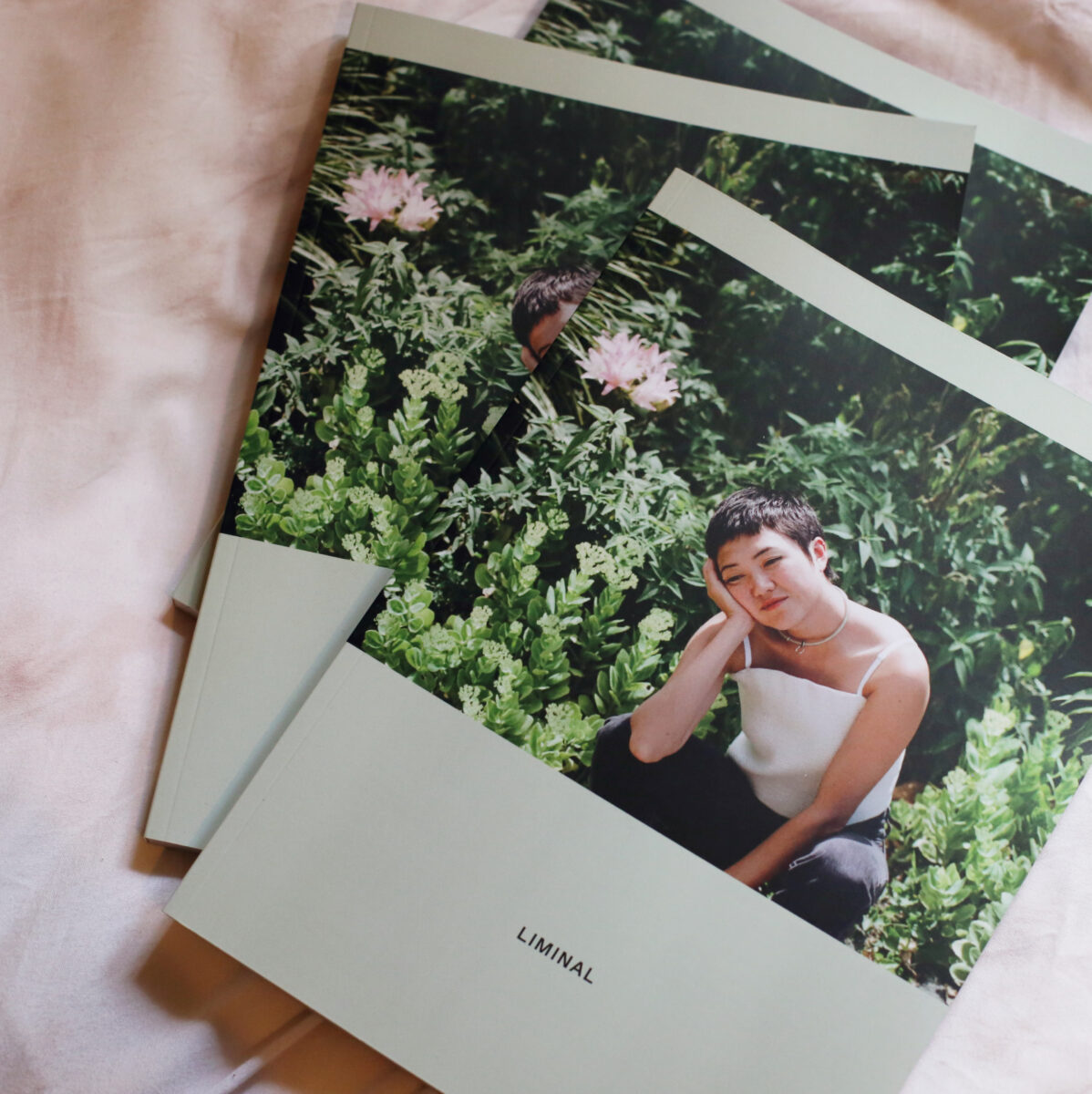

According to its website, ‘is an anti-racist literary platform, publishing art, writing, interviews & more’. It aims to ‘support talented writers and artists in so-called “Australia”, with a focus on the Asian Australian experience.’ For its founder, Leah Jing McIntosh, ‘The impetus for Liminal, which was founded in 2016, came out of a desire to see more people and to hear more voices that were a little more like mine.’

Among Liminal’s many projects are their longform interview series, the Liminal Review of Books, their national writing prizes, and their subsequent collections, Collisions: Fiction of the Future (2020) and Against Disappearance (2022) with Pantera Press. Liminal’s long-running interview series features creatives of colour including an interview with Jon Tjhia, who is also a Liminal writer and guest editor.

So what does it mean to be an explicitly anti-racist project? And what potential does it open?

McIntosh points out that the Liminal project was not set up with a sole focus on ideology. ‘First and foremost, I wanted to create work I wanted to see in the world; I wanted to have some fun, to make something with likeminded artists and writers and thinkers. Of course, anchoring this desire is a strong interest in racial justice, equity, equality. I wanted to understand and dissect how the literary industry intersects with legacies of white supremacy; how these structures dictate what we read, what we write, what work wins prizes, what work is held up as excellent within the literary culture of this country.’

For McIntosh, anti-racism is not something that can be ‘achieved’ and ticked off the to-do list. ‘It is not a noun, it is a verb. It is an action, it is always in motion, it is something you must commit to every day.’

Jon Tjhia agrees. ‘It’s ongoing work, not a thing you can solve by making a gesture or three,’ he says. ‘It’s hard because it doesn’t really let up – you don’t get to say you’ve solved it and it’s done now. Instead, it becomes part of your work.’

For McIntosh, the work of anti-racism has two prongs. The first is about acknowledging marginalisation. ‘It’s important to acknowledge that the industry we work in, at times both with and against, is not made for us. Working with the literary industry, it’s imperative to acknowledge that racist legislation— such as the White Australia Policy—might have been repealed, yet it still casts a long shadow’ she says.

Tjhia agrees. ‘It’s about recognising that we each exist within an ecosystem of ideas and behaviours and there’s no real escaping that. It’s baked into the money we earn, the things we buy, whose labour we value at what amount, the governments we must live with and the implicit meanings of things we see.’

The second prong of anti-racism work is about recovering the creative work that is lost due to this marginalisation. ‘There is so much talent which has already been lost or gone unrecognised, and there is still so much that we cannot afford to lose,’ says McIntosh. So, of course, we must first acknowledge the impact of the colonial project on the literary industry. So Liminal is an attempt to intervene, to make considered interventions within this racist and racializing framework, even if it does feel like—such small attempts, some days. ’

The dilemma of representation

One of the key focuses of arts organisations working to improve racial equity is to increase representation, both of their staff and the artists they support. However there are many pitfalls in trying to retrofit an unrepresentative organisation, including tokenism, issues with cultural safety and pressure to ‘perform your identity’, which can contort work.

According to Tjhia, ‘The artistic and cultural mainstream of so-called Australia centres certain traits including whiteness, which means that for decades, artists who aren’t white have been creating work that overcompensates for imaginary white audiences. That might take the form of self-exotification, self-dismissal, over-explanation or translation, or in some cases shame or self-mockery. Racial shame can be sublimated into parallel forms of self-sabotage too – like leaning into perceived expectations of gender identity, physicality, class politics.’

‘Sometimes we receive pitches from people of colour, which is wonderful, because it’s nice to see how far this project has travelled,’ says McIntosh. ‘But what we’ve found is that, unfortunately, often young writers of colour only feel comfortable to pitch writing around racialized trauma. This is not their fault; they’ve been fed the lie that racial trauma is the only the only thing they can write about.’

‘I think oftentimes when we think about what ‘representation’ means, it is representation of racial trauma. So, from the beginning, I wanted Liminal to move beyond that. It’s not that we’re not acknowledging racism or trauma! Of course we are. It’s why we exist! But it’s just that we’re also far more interested in what joy looks like, in what love looks like, in what existential crises look like, in what living in this world looks like. We’re refusing to be flattened into another racist trope. So we aim to publish writing and art and criticism and interviews that brings this fullness to the page’ she says.

Another issue is the effect of data collection, which aims to demonstrate representation. Tjhia says, ‘I think this is particularly complicated – not just performing your identity but having to declare it in the first place. As a friend said to me the other day, I didn’t think of myself as different until an application form reminded me. If I tick the ‘culturally and linguistically diverse’ box, one door opens and another door closes; the door that closes is my ability to choose what I centre. I’m not diverse to myself, am I?’

Very often organisational attempts to improve equity can morph into measures that maintain existing power structures, or are hollow virtue signalling. According to Tjhia, ‘You can learn inclusive or person-first language or whatever, but the things you use it to say can still be a mess. The point of those things is to encourage you to think differently – it’s a structuralist view of language – but in my experience, sometimes that just helps people feel more confident in saying things that are cooked. So – language does matter but no one action like that is going to fix things.’

For McIntosh, these are the sorts of issues that can send organisations scrambling. ‘It must just absolutely freak out white organisations, and they must have meetings about sensitivity readers and how we can look more woke and how we can be better in the industry without actually giving people of colour positions of power. Let’s just put on a band-aid.’

Beyond representation

As an organisation where power is held by people of colour, with anti-racism as the foundation, Liminal has avoided much of this kind of angst. It means that Liminal is free to focus on the art.

‘I think a lot about how representation is just the first step. I think for a lot of Australian arts organisations, unfortunately, representation is instead their end goal,’ says McIntosh. These last six years, the Liminal project has pointed out, time and time again, that there is so much more. We want to move beyond reductive representation, in order to shift this country’s very eurocentric imaginary into something we can all be a part of; which we could all be proud of; I think this should be one of the goals of ‘representation’, too.’

According to Tjhia, ‘Getting past the basics means you’re freed up to think about the actual work.’

What is the Imagine Project?

We’re publishing case studies and documenting Australia’s best work in advancing cultural diversity and racial equity and inclusion in the arts through the Imagine Australia Project, managed by Diversity Arts Australia (DARTS) and funded via the Australia Council’s Re-Imagine project and supported by Creative Equity Toolkit partner, British Council Australia. To find out more click below – or read the other case studies as they go live here.