A richer past is made available to us through these forty voices – and a richer future. What a gift this is in our world today. Words that ground us in the land we inhabit, but also a land we could aspire to inhabit.”

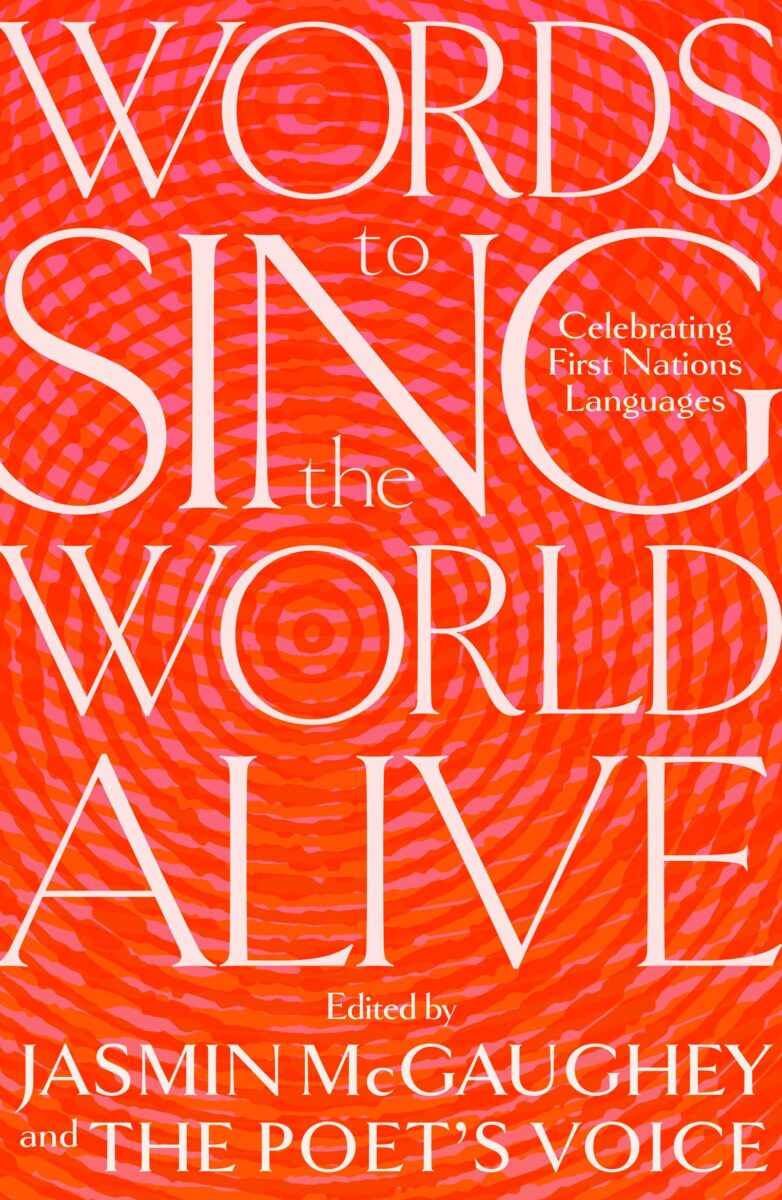

Words to Sing the World Alive (2024) edited by Jasmin McGaughey and The Poet’s Voice is an anthology of forty First Nations writers, thinkers, artists and journalists celebrating First Nations languages around the continent. Each writer selects their favourite, significant word in language, with the name of the anthology taken from poet Jazz Money’s chapter, which offers a moving summation of truth-telling in a single word. Language connects Country, and in turn, this collection explores the history of this continent from nature to people to story.

Contributors range from literary stalwarts like Ellen van Neerven and Dr. Anita Heiss to performers like Wagadagam actor Jimi Bani as well as activists like Indigenous Officer of the Maritime Union of Australia Thomas Mayo. Jasmin McGaughey’s foreword sets the tone for what to expect in this unfolding exchange of language.

The concept underpinning the anthology is its beating heart: that First Nations languages are explored and inhabited through words that form on the tongue. Language is not only evocative but is deeply connected to natural cycles, tides and even animals. The words chosen by the speakers guide our understanding. The index of words also shows how they can vary over Country.

Amai, the Kalaw Lagaw Ya word for cooking in a ground over hot stone, iterates ‘the bond between island men, and the act of feeding families’ from father to son. From Warakurna, Western Australia, Dr. Elizabeth Ellis introduces Tjukurra – synonymous with mirrl-mirrlpa (sacred). The word is held in conjunction with creation time – the First Nations concept of Dreaming. It also refers to other meanings, from the landscapes and features of the environment to the stories carried from birth and from totem. Though Ellis offers her own definition, she also features additional anthropological insight from expert Fred Myers. He says:

“Because the Tjukurrpa touches on so many dimensions of Western Desert people’s lives, it possesses no single or infinite existence. Instead, it represents a projection into the symbolic spaces of various social processes, hence the social meanings of the Tjukurrpa only become apparent in the penetration into every aspect of Aboriginal life, by providing a guide to all social order, social activity and communication.”

This extension of language is significant. While it is an extensive catalogue, each word is a signifier wielding non-hegemony as it champions the richness and enormity of the First Nations history.

Other entrants are less literal in form. Jack Latimore’s introduction to the word Waarki is a haunting excerpt from his personal life, depicting his brush with a folkloric monster known as a skinned man. When looking for the definition in the Gathang dictionary, he found Djagiri (devil-spirit), Dulagal (spirit), and Goi-on (devil-monster who punishes on consequence), but no Waarki. When he asks his elders why, they mention that its reclusive origins probably came from elsewhere and socialised itself within his people when they were impounded on Christian missions. He finally finds his answer from an old man on Gomeroi land who inspects the frequency of a fallen scar tree:

“From the fringe of the desert, it comes from the south-west of my Country…He is one of the hybrid people who came down from the sky to scuff the children up.”

The interconnectivity of Words to Sing the World Alive deepens our understanding of how First Nations language has always involved interplay. These collisions are not only cross-cultural and referential across different peoples: they are song and poetry and sociological records. The words shared in the book all point to survival, joy, resistance and preservation – they earmark the makings of the world’s oldest populace, whose stories are ancient and still emerging today.

First published by Aniko Press on March 12 2025. This article has been commissioned in partnership with Diversity Arts Australia’s StoryCaster project, supported by Multicultural NSW, Creative Australia and Create NSW.