Ordinary Ascension – A Hope by Khaled Sabsabi

Review and Interview by Adam Phillip Anderson

Community affects our lives before we begin to exist. The idea of the self, arises from people and places that instil our social values, inspire our beliefs and shape our reality. Common causes, shared experiences and mutual connections bring communities together. Difference, conflict and grievances break communities apart.

Khaled Sabsabi’s solo exhibition A Hope, exhibiting at Campbelltown Arts Centre until 17 March, collects two decades of an artistic practice that keeps community cultural engagement at its core. It is a multi-sensory experience where process and product, medium and meaning, concept and construction are blended into one fluid expression of human experience.

As a Lebanese Australian multidisciplinary artist working with sound art, installation and theatre, Sabsabi’s work is informed by community connection and deals with contemporary social and political concerns. Born in Tripoli, Lebanon, he and his family migrated to Dharug Land – Western Sydney – where he continues to live and work. As an adult, he travelled back to Lebanon and around the world, reconnecting with his traditions, culture and ancestry.

In addition to visiting A Hope I had the pleasure of interviewing Sabsabi. I asked him how his two homes, Tripoli and Western Sydney, influence his work:

“Both places are dear to me. They are where I call home. Both places are very rich in history and tradition. In this place and in Tripoli, history is ancient. In Western Sydney, it’s the migrant history and cultural diversity and the working class.”

The path and choices of Sabsabi’s life inspire me to maintain connection to my own Javanese roots from my homes on Dharug and Gamilarray land.

Entering the art centre, A Hope is first heard then seen. Drums and chants of the “Red Black Bloc” (RBB) – Western Sydney Wanderers’ dedicated fan base – rumbles through the foyer. In the first darkened chamber of the exhibition, two large screens display Wonderland (2014), a video installation streaming vision of the RBB cheering for the team on match day. The RBB is a wave of cropped hair, bare chests, tattoos and raised arms. Each eye is wide and ablaze, each mouth adding to one great, unified sound. With his back to the viewer, a bald man wields a megaphone, occasionally resting it on his broad shoulder while leaning down to talk to the man at his right hand. Amongst the zealous, chaotic energy of the crowd I can sense a feeling of commonality and trust. A mutual respect between leader and group. I wonder about each man’s story. What he has seen. Where he stays. Who does he look after and who looks after him? As I watch the watchers, I think about the parallel values of football and community. Communication. Co-ordination. Cultural and economic inclusion. Physical, mental and spiritual health. People coming together, for reasons beyond themselves.

From here, the exhibition is laid out with a winding linearity, like a cave. Each work is like a challenge or trial. Roughly speaking, the works move from loud to silent, concrete to abstract. This world to another. I asked Sabsabi about the role that physical space plays in his exhibitions:

“You’d be a fool not to take space into consideration, especially considering where we live on unceded, stolen land. Space is politically charged. There is disposession, genocide, and apartheid states that keep flourishing. There are many deals that need to be rewritten. Its arts job to do that. There is no art without context.”

The second installation, Mush (2012), is a collection of travel images arranged through pattern and repetition into a four-sided, portal-like prism. Scrolling landscapes, ancient and modern architecture, people, places, art and nature. Organized into one overwhelming artefact. I spot the floating fabrics of a whirling dervish amongst trees, skies, windows and ceilings. On the wall behind this arrangement, the same variegated pattern of light is processed into indistinct exposures contained within concentric, slowly rotating squares. The images combine with an ethereal underscore of ambient music to evoke the feeling that the viewer is about to be transported beyond their current state of existence. The RBB still roars behind the gallery wall. A reminder of the concrete world.

I asked Sabsabi about sound in his work:

“My video work is still hip hop. It’s still sampled. Patterns and sequences laid down like a track on a drum machine. Hip hop is about the alternative. Sound and music is the language of the universe. The room for imagination materialises in our ability to hear things.”

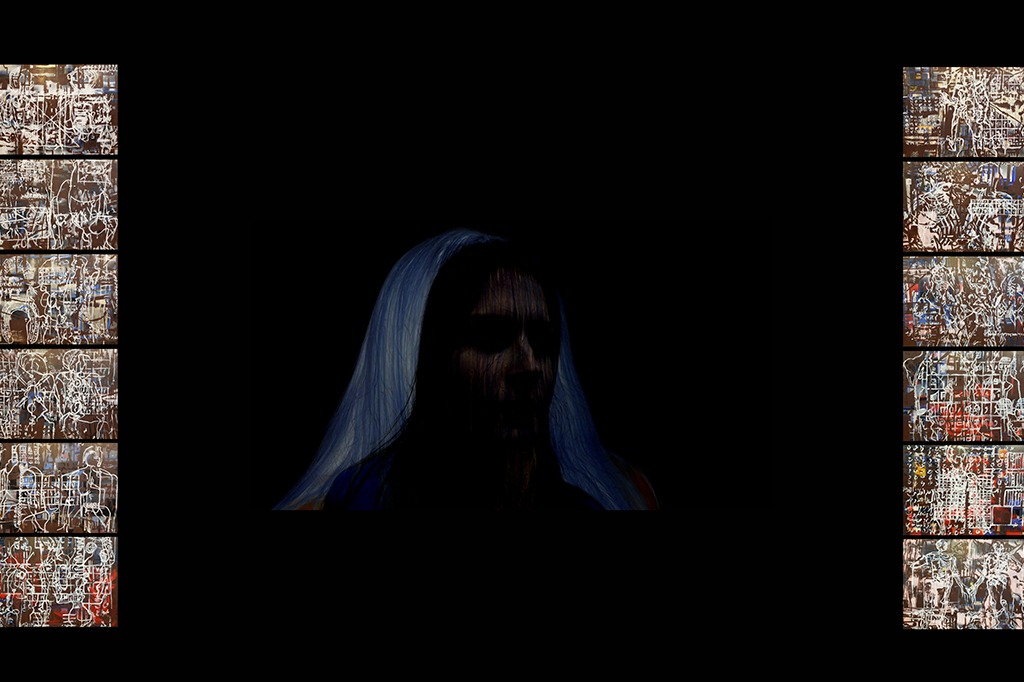

In the next chamber, the dream-like images of 40 (2020) – two enormous video projections – span two opposing walls. As the visions shift with a pondering pace, a floaty, humming soundtrack makes time feel warped and unimportant. Between these projections hang 18 similar but unique double-sided paintings. They show painted images etched in white. Systems of the body. Skeletal. Circulatory. Nervous. Digit tables. Sequences of letters. Similar patterns are displayed on postcard sized paintings numbering 40 across two walls. Counting the two projections, both sides of the 18 large paintings, and each set of 40 postcards as one: The displays add up to 40.

On screen, I watch bare feet walking over sand. The camera tracking with a hypnotising sway. Naked bodies fall down, slumping in deep rest or death. Someone washes their hands in the dust of three moons. A crowd of veiled shadows, are they looking toward me or away? Faces are never fully visible. A woman is screened in a texture like running paint, a negative blue shadow framing her darkened profile. A white fabric cloak has a face of fallen leaves. The second projection displays landscapes. A stony cliff-face. A vast desert. Ripples of the ocean. As I cross the room the projector catches my silhouette. Were these scenes left empty, just for my shadow?

I asked Sabsabi about the placement of the viewer within his works:

“The exhibition puts the viewer in an in-between space. It makes the human viewer choose within the works to move left or to move right. In 40, the subjects look left and right, left and right while being engulfed by the sea. A Self Portrait (2014-2018) scrolls right to left. They symbolize east and west, right and wrong. It gives the viewer a moral choice. To absorb or to reflect. Within humanity these extremes will always exist. Love and hate. Construction and destruction. There’s always a possibility, although others have done the wrong thing, to change things through activism, through choices. The choice is always there.”

40 conveys a tension between 4 and 0. The everyday and the infinite. The intricate patterns of our bodies and the complex systems of the mind. This is an expression of all aspects of being: the viscera of the body, the complexities of thought, the confusion of dreams and the mystery of emotion.

Passing through a narrow corridor, 8.4.9.1 (2019) hides between the two largest chambers. The images of violence, hatred and injustice challenge the viewer’s decision to push on. Here, the megaphone as a symbol recurs in different context. How does the empowerment and camaraderie of Wonderland look when people are coming together to take others apart?

Moving on, Bring the Silence (2018) depicts worshippers performing a ritual inside the Maqam of Muhammad Nizamuddin Auliya. I take my shoes off to walk around the woven plastic mats covering the floor. The viewer’s path mirrors the mourners onscreen: four projector screens are like the chamber’s four walls, one screen lays flat like the grave. Each screen displays the holy site from a different perspective. Inside, a parade of bare feet files silently around a mound of flower petals and silk. Hands offer prayers, touch the mound, then their hearts and foreheads.

From here we have left the concrete world and entered the unseen. These works communicate the tradition of Tasawwuf which, to my understanding, is the inner dimension of spiritual devotion which aims to engage with the divine with a deep consideration of human emotionality and subjectivity. The sound of Ziker – devotional chanting – from Naqshbandi Greenacre Arrangement (2011) fills the aural space. Divine Victory (2012), positioned again with intention, challenges our progress with its interrogation of our role as observers and interpreters of our world. Finally, Beyond At The Speed of Light (2016) sits in the last, quietest chamber, communicating Sabsabi’s ultimate contemplation of the divine and unknown.

I asked Sabsabi about the intention behind the show’s layout:

“The spiritual relationship is really important especially in a solo show like this one. In a solo show you’re mapping out an entire narrative. Looking at the lines, shadows and thresholds. The way this is constructed, its like life for me. I wanted to map or replicate the idea of life. We come into life, we go through life, we observe, we grow, we love and through those experiences were aware of our emotions and intellect. Its how we negotiate and create change in the world.

At the end you have to retrace the exhibition. Like life and death. A cycle. Having the possibility to look back and reflect on their life. Very few people have this opportunity. It’s like a luxury item you pay for by listening. Observation is one thing, reflection is another.”

In an age of isolation, social despondency and anxiety, it’s easy to stop believing, to give up. Sabsabi’s work is a reminder that transcendence is still possible within the ordinary. That connection and community can always be chosen over hatred and separation. That a world marked by devotion and kindness exists and long as it can be envisioned.